Physicians and environmentalists alike could soon be using a new class of electronic device: small, robust and high performance, yet also biocompatible and capable of dissolving completely in water – or even in bodily fluids.

|

| Biodegradable electronics that vanish in the environment or the body |

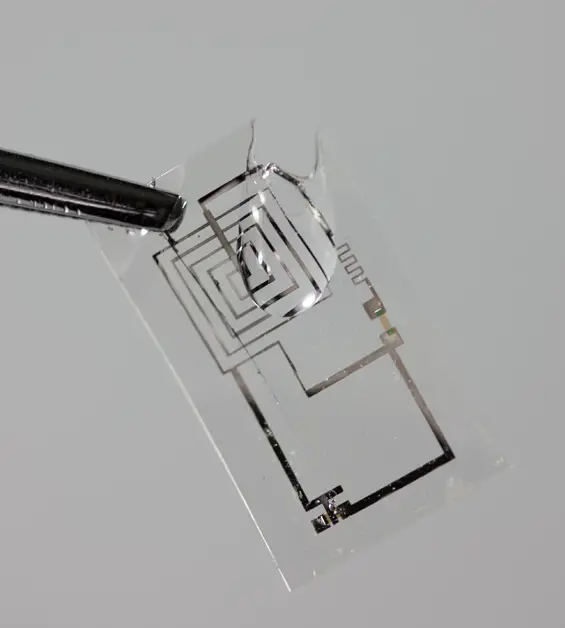

A biodegradable integrated circuit during dissolution in water. Photo courtesy of Beckman Institute, University of Illinois and Tufts University

Researchers at the University of Illinois – working in collaboration with Tufts University and Northwestern University – have demonstrated a new type of biodegradable electronics that could introduce new design paradigms for medical implants, environmental monitors and consumer devices.

"We refer to this type of technology as transient electronics," said John Rogers, the Lee J. Flory-Founder Professor of Engineering at the U. of I., who led the multidisciplinary research team. "From the earliest days of the electronics industry, a key design goal has been to build devices that last forever – with completely stable performance. But if you think about the opposite possibility – devices that are engineered to physically disappear in a controlled and programmed manner – then other, completely different kinds of application opportunities open up."

Three application areas appear particularly promising. First are medical implants that perform important diagnostic or therapeutic functions for a useful amount of time and then simply dissolve and resorb in the body. Second are environmental monitors, such as wireless sensors that are dispersed after a chemical spill, that degrade over time to eliminate any ecological impact. Third are consumer electronic systems or sub-components that are compostable, to reduce electronic waste streams generated by devices that are frequently upgraded, such as cellphones or other portable devices.

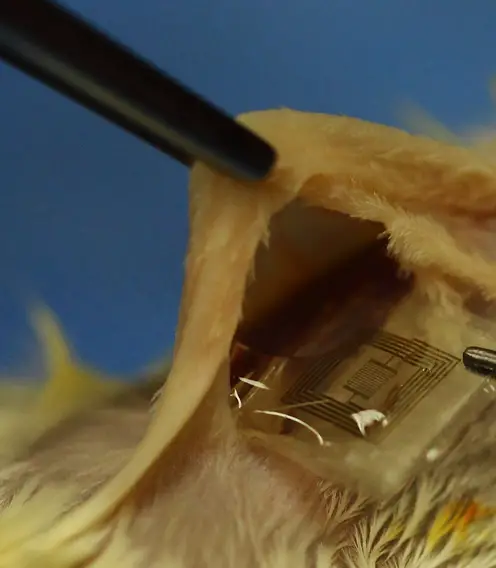

A biodegradable integrated circuit is implanted under the skin of a lab rat. Credit: Beckman Institute,

University of Illinois and Tufts University

Transient electronic systems harness and extend various techniques that the Rogers' group has developed over the years for making tiny, yet high performance electronic systems out of ultrathin sheets of silicon. In transient applications, the sheets are so thin that they completely dissolve in a few days when immersed in biofluids. Together with soluble conductors and dielectrics, based on magnesium and magnesium oxide, these materials provide a complete palette for a wide range of electronic components, sensors, wireless transmission systems and more.

The team has built transient transistors, diodes, wireless power coils, temperature and strain sensors, photodetectors, solar cells, radio oscillators and antennas, and even simple digital cameras. All of the materials are biocompatible and, because they are extraordinarily thin, they can dissolve in even minute volumes of water.

The researchers encapsulate the devices in silk. The structure of the silk determines its rate of dissolution – from minutes, to days, weeks or, potentially, years.

"The different applications that we are considering require different operating time frames," Rogers said. "A medical implant that is designed to deal with potential infections from surgical site incisions is only needed for a couple of weeks. But for a consumer electronic device, you'd want it to stick around at least for a year or two. The ability to use materials science to engineer those time frames becomes a critical aspect in design."

Since the group uses silicon – the industry standard material for integrated circuits – they can make highly sophisticated devices in ways that exploit well-established designs by introducing just a few additional tricks in layout, manufacturing and supporting materials. As reported today in the journal Science, the researchers have already demonstrated several system-level devices, including a fully transient 64-pixel digital camera and an implantable applique designed to monitor and prevent bacterial infection at surgical incisions, successfully demonstrated in rats.

Next, the researchers are further refining these and other devices for specific applications, conducting more animal tests, and working with a semiconductor foundry to explore high-volume manufacturing possibilities.

"It's a new concept, so there are lots of opportunities, many of which we probably have not even identified yet," Rogers said. "We're very excited. These findings open up entirely new areas of application, and associated directions for research in electronics."

Post a Comment